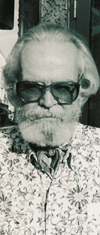

The floral shirt, cravat, flowing white hair and thick-rimmed glasses suggest he might be, say, a neo-impressionist painter. Perhaps, a lazy maker of trite landscapes to sell to American tourists. The truth could hardly be more removed. Throughout his film career, Vatroslav Mimica perpetually challenged aesthetic and formal conventions, even defying his own style. Frequently collaborating on the screenplays to his films and always heavily involved in the editing, Mimica became one of the most significant auteurs in Croatian film history. Earlier this year in June, the 48th Pula Film Festival honoured Mimica with a life acheivement award and a retrospective of his pioneering 1950s and 1960s work in recognition of his talent. And it was here that I met Croatian arch-modernist, now in his 78th year, to discuss his film career, from which he retired more than 20 years ago.

From medicine to film

Mimica was born in 1923 in Omiš, a picturesque old mediaeval town near the Dalmatian port of Split which was to inspire the scenary of some of his later work—most notably his feature film Kaja, ubit ću te (Kaja, I'll Kill You, 1967). He was educated first in Split and then in Zagreb, where he has lived since 1930, becoming a medical student in his higher studies. In 1942, following the German invasion, Mimica joined the underground anti-fascist movement and the following year joined the partisan Liberation Army, where he served in the medical corp.

After the war, he continued his study of medicine, but in his spare time he worked as a literary critic and journalist, founding the first student newspaper in Zagreb. As an energetic young man with an impeccable political background in the partisans, he was made general manager of Jadran Film, the Croatian production company, in 1949. Mimica, however, was not content with overseeing the general running of the company, and started to learn the art of film-making. He worked as general manager for two years, but, dissatisfied with the bureaucratic system, he decided to become a freelance film-maker, a way of working he was to stick to throughout his career.

Mimica, thus, entered film-making without any formal film education. Instead, he learnt from the masters:

I analysed classic films by looking at them frame-by-frame on the editing table. For example: the films of David Lean, from whom I learnt dramaturgy; or Billy Wilder, from whom I learnt mise en scène, he is a great master of mise en scène. So when I did my first feature film, I was not unprepared. Of course, I was not so self-assured in all things, but nobody knew that except myself.Resistance in animation

After his first two films—a melodrama U oluji (1952) and Jubilej gospodina Ikla (The Jubilee of Mr Ikel, 1955), a comedy—he made a break and started working in animation, just as the animation film section of the Zagreb Film studio was being established. His first animation, Strašilo (Scarecrow, 1957), was done in the orthodox Disney style of its day. But this was to change with his later films. Samac (Alone / The Bachelor, 1958), his next film, took contemporary graphic design as its starting point and used a Kafkaesque nightmare of isolation in a bureaucratic system as its subject matter. It was the first of several dialogueless animations he made that used an imagined visual world to try and express the abstract emotions of this real one, rather than simply tell a story.

Even now, as Mimica is keen to point out, these films look modern. "Their different approach," the director explained, "was a reaction to the ideologism and regimentation of the time. For me it was a form of resistance." Film-making itself was not without its bureaucracy, and Mimica said that every film project he realised had to go through a battle with an approval commitee before he could make it. "But whenever I got the approval for making the project," he also noted, "I had completely free hands to do what I wanted. It only was a matter of getting the film approved. I never had someone behind me watching what I was doing. Never. And nor had the other artists."

Even now, as Mimica is keen to point out, these films look modern. "Their different approach," the director explained, "was a reaction to the ideologism and regimentation of the time. For me it was a form of resistance." Film-making itself was not without its bureaucracy, and Mimica said that every film project he realised had to go through a battle with an approval commitee before he could make it. "But whenever I got the approval for making the project," he also noted, "I had completely free hands to do what I wanted. It only was a matter of getting the film approved. I never had someone behind me watching what I was doing. Never. And nor had the other artists."

Furthermore, Mimica had an advantage that his colleagues in, say, Czechoslovakia (with whom, incidentally, Mimica was in contact with) did not have: Yugoslavia had split from Stalinism in 1948 and as a result Party cultural policy was not dominated by Socialist Realism, as it was in other Communist countries. "There was no official art and there was little censorship, although there were other indirect forms of censorship, for example you were neglected."

Festival successBut Mimica couldn't be neglected. He had Europe-wide support and interest in his work, thanks to the festival network. In part, this was due to an enormous risk on Mimica's part:

For my first presentation of an animated film at Cannes, in 1958, we didn't get official permission to show the films. I'd been in Paris the previous year, and I had very good contacts there. They invited me and our films, of the Zagreb Film School, to be projected at a special screening at Cannes. So, I just smuggled the film to Cannes. It was very risky, but I did it. And if the films hadn't succeeded, I would have had big problems [with the authorities].

The screening was a success, though, and later that year Mimica picked up an award for Samac in Venice. With so much international attention on Mimica and the Zagreb Film School, his films could not be shoved under the carpet domestically. Samac was shown at Pula, where it was praised for its modernism and liberalism, and Mimica received the first of many awards from the festival. In the context of a 1950s Communist country, this was all the more remarkable. The Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 was still in the mind of every Yugoslav citizen, and there was a very real fear that too liberal a regime might lead to the Russian tanks rolling across Europe once again.

The return to featuresAfter making a cycle of seven or eight animations, Mimica decided it was time for another change of direction and returned to the larger canvas of feature film: "it's like the passage from writing a letter to a novel." His first feature film and this second wave was an Italian film, Solimano il conquistatore (Suleiman the Conqueror, 1961), which starred Edmiund Purdom, an Egyptian actor who was popular in Italy at the time, and Georgia Moore, the American actress ("it was fashionable to have American acresses in Italian films at that time"). It was a huge sucess in Italy. But it was a highly conventional film (although Mimica insisted it was a more realistic than the standard Hollywood treatment of historical subjects), and despite its box office success, Mimica was again not satisfied: "I didn't want to spend my life on that rail," as the director put it.

So, Mimica returned to Croatia to make his first modernist feature film, Prometej s otoka Viševice (Prometheus from the Island of Viševice, 1965). The film tells the story of a Communist official, Martin, returning to the island where he spent the war for a ceremony to cememorate the Partisans, of which he was a member. As he travels back, a flood of memories returns to him, and many are far from happy ones. First they come in no particular order—an unexplained montage of arresting and sometimes disturbing images. Gradually, the story is pieced together to reveal, and the memories fall into place in the viewer's understanding. After the war, Martin became a Party functionary, but meets opposition from the conservative islanders for his well-intentioned plans to introduce electric lighting, with tension gradually turning to direct confrontation, while the Party are unable to give him the support he requires from them.

Despite an ending obviously tacked on in order to gain oficial approval, the film is a critique of the rigid Communist bureaucracy and its distance from the people while never losing sympathy for the individual humans involved in the Party. The film is also notable for its strong ethnographic approach, using local dialect and trying to accurately recreate the way of life of the islanders.

I put it to Mimica that the film showed the influence of Michelangelo Antonioni and the exploration of memory evident in the work of Jan Němec. However, it's often dangerous to ask a film director about the connections between their work and someone else's: they usually deny it. Mimica had no problem with acknowledging the place of the Italian Neo-realists in cinema of the time, but prefered to talk about influences in terms of the collective consciousness of the age:

It was a similar spirit, in the Czech Republic there was Miloš Forman's Lásky jedné plavovlásky [A Blonde in Love, 1965] and in Hungary there was [Miklós] Jancsó. It is difficult to say who influenced who. It was a spirit in the air.A day in the life of

His next feature film, Poneđeljak ili utorak (Monday or Tuesday, 1966), retained many features in common with his previous one: formal experimentation, an interest in depicting the processes of thought through dreams, fantasies and memories and the capturing of echoes of the war in present-day experience. This "day in the life of" style film follows a Zagreb journalist Marko, or rather his mental processes, thus creating Mimica's least conventionally plotted film.

In contrast to Poneđeljak ili utorak's predecessor, the film is more interested in the mundane, concentrating on everyday life, rather than the epic internal struggles of some "Prometheus." Gradually, we come to piece together Marko's hopes and fears; the daily concerns of paying the rent sitting alongside wider fears of world war and memories of the difficult century that Europe is experiencing.

We also learn about his private life: his former wife; his current girlfriend Rajka, whom he is constantly trying to contact; and his feelings for an unknown he sees standing at a bus stop, waiting in the rain, who causes him to remember a poem by Jacques Prevert as he loses himself in mild reverie. The film ends with him putting out the light to go to sleep, having watched Rajka on television read the end-of-service announcement.

Some of the devices now seem a little dated. Changes in image quality and colour are probably less exciting now than they were then, and the intercutting of documentary footage of the concentration camps particularly now has a somewhat heavy-handed and "obvious" feel to it. But the film still exudes the appeal of what the New Wave must have looked like when it first emerged as a trend, with its concentration on ordinary people and charmingly observed street scenes. And its this that makes the film endearing. There's none of the removed coldness that formal experimentation can bring to a film as an unfortunate by-product.

A study of evilWith Kaja, ubit ću te (Kaja, I'll Kill You, 1967), Mimica returned to the Dalmatian islands and a film set in the war-time era. It follows a, perhaps, rather straightforward plot outline of a group of close friends who are driven apart by war, or rather in this case the Italian occupation of Dalmatia. Here, the chief conflict is between Lovore, an under-acheiver who failed to finish school and finds that fascism gives him a place in life, and Kaja, the laconic dissenter who pushes the regime too far and pays the price, as the film's title is not shy about revealing.

As previously, Mimica makes up for a simple scheme by concentrating on details. As well as returning to the islands, he also returns to the ethnographic approach of Prometej s otoka Viševice and retreats from New Wave aesthetic of contemporary, urban culture. Here, the focus is life as it has been for centuries, both human and natural, with the camera spending time to explore the non-human inhabitants of the island. There's also a heavy emphasis on historical tradition, with the brutishness of the fascists contrasted with the beautiful religious stone carvings of the historic island of Trga, where the action takes place.

The film was not received well at the time, however—a reminder that Pula hasn't always been so kind to Mimica:

Pula used to be something like football matches in England, the amphitheatre was packed, and it was a mob psychology. Two years before Kaja, ubit ću te, Prometej s otoka Viševice got the audience award because the audience recognised the critical elements in the film and two years later they didn't make the connection with Kaja, ubit ću te. Some people started whistling. I even got hit by a stone [that somebody had thrown at me].

Although the intentions of the film are now clearer, it has still dated in some respects (for example, in the film's climax, with the image of Kaja's flailing body as he grasps for support, having been shot). Moreover, the trope of friends driven apart by war has been used by a number of films with greater success—Lordan Zafronović's Okupacija u 26 slika (The Occupation in 26 Pictures, 1978), to give a Croatian example.

However, most of the films to which Kaja, ubit ću te can be compared actually were made it. One comparison to have dogged the film is with Felini's Amarcord (1973). As Mimica was keen to point out:

I presented Kaja, ubit ću te in 1968 in Naples, where I received the golden award, and after the screening one man approached me and said that he was a farmer, but he also wrote screenplays. And that was Tonino Guerra, the great Italian scenarist, who five years after that wrote Amarcord. We've always remained great friends.

Also worth bearing in mind is in the context of the film's time. Kaja, ubit ću te human focus and its subtler and more disturbing vision of how good wins out over evil made it a different from most pictures portraying the fight against fascism, especially the triumphalist Partisan films. In this respect, it is more of a story that just happens to be set in the war period, and Mimica can rightly say, "I have not made any war films."

Going back to natureHaving made three films marked by their modernist use of structure, Mimica then reverted to more traditionally plotted films. The first of these, Događaj (The Event, 1969), is about a farmer Jure and his grandson Marian. The boy, having lost his father, lives in perpetual fear that he will lose his grandfather, too. When Jure announces that they will have to go to town to sell their horse, Marian is filled with a horrible, prescient feeling that his worst fear is about to come true.

The trip starts well: the horse is sold for 3000 dinars and Marian buys a radio and forms a friendship with a girl who can speak backwards. On the return journey, it becomes apparent that Jure and Marian are being followed. Despite trying to lose their pursuers, Jure is forced to fight them hand-to-hand while Marian runs for his life. The fight ends with Jure being knifed.

Marian is given refuge by a ranger's wife, but the house he has stumbled on harbours two coincidences: the ranger's daughter is the girl who could speak backwards and the ranger is one of his father's killers. The other killer is far from happy that the crime has a witness, and demands he be silenced forever.

The film, becoming more conventional as the action procedes, yet again focusses on nature:

I wanted to introduce into this film my feeling towards nature which I felt as a young partisan. I am a town child, we went into the woods in the Second World War, we slept in the trees, we were marching through the mud. And I think I've shown that in this film.

But the obvious question is why, after a decade of making films with a decidedly avant garde slant, did Mimica suddenly change tack? Mimica himself sees no contradiction in this change, and indeed views it as a positive development:

Before animation, I did two feature films, and they were made in a conventional manner. I was captured by the story; I was a captive, like a fish in a bowl. I was in the middle and the story was around me. After the experience of animation films and my first three [modernist feature] films, I found myself in the position that I can rule over the story. And the story was only one of the elements of expressing myself. I could be out of the story, and the story didn't capture me.The people's dictator

The most recent of Mimica's feature films to be shown as part of the Pula retrospective was his 1970 picture Hranjenik (The Fed One). It is another film set in the war period that refuses to adopt the orthodox style of Partisan films. The action here centres around a concentration camp.

The inmates of one dormitory are victimised by their Kapo (camp guard employed from among the prisoners). They have no hope of rising up against his victimisation, as they are all too underfed and weak. They, therefore, decide to all give a portion of their meagre rations to the strongest among them, and make him fit and strong. But the plan backfires when the "fed one" uses his strength against the people who have made him strong, forcing them to turn to the man who once seemed certain to destroy them.

Again criticisms can be made of the picture. It is quite clearly a non-realistic view of the concentration camps. The sense of order, free space and even cleanliness portrayed in Hranjenik is clearly in start constrast to both reality (as shown, for exmample, in the documentary clips that appear in Mimica's own Poneđeljak ili utorak) and earlier films set in the concentration camps such as Pasażerka (The Passenger, 1961) by Andrzej Munk (a director whom Mimica went out of his way to praise in the course of our conversation) .

If there is a justification for this lapse, it is that Mimica in this film is only marginally interested in the Second World War. Hranjenik is plainly trying to establish a deeper study of the concept of evil, rather than depict specific historical realities (although it should be noted that in Kaja, ubit ću te he succeeds in doing both without one impinging on the other). The comparison with Partisan films is again revealing, and the film strongly suggests that evil does not eminate from fascism as some absract elemental force in the universe but from human free will. As Mimica phrases it, "The film acts as a global metaphor of totalitarianism, which has its roots in human beings."

Such musings on the nature of totalitarianism were not entirely appreciated in Communist Yugoslavia. Recalling the reception of the film with a certain amount of detatched merriment, Mimica said:

It was predicted to get the main award from Pula from the jury—it was shown at the beginning of the festival—but someone at Brioni island [near Pula] where Tito resided saw the film and recognised the situation of the film. [After that] nobody spoke about the film. It was silence; as if the film didn't exist.The battle between empires

Having returned to a more conventional narrative form in the late 1960s, Mimica ended his career by returning to costume drama, continuing on from his successful first feature Solimano il conquistatore. None of these late films were shown as part as the Pula retrospective, but it is certainly worth mentioning his last two features.

Sedlačka buna 1573 (The Peasants Uprising 1573, 1975) was based on a historical event in the northern part of Croatia and inspired by in its schematics by the art works of Pieter Bruegel. The film was based on Mimica's own historical research (rather than just using a Romantic 19th-century Croatian literary account of the event), and as with previous films, Mimica was keen to pay attention to detail. By sheer luck, they were able to gain some of the best costumes on the market at a nominal cost when the owner of the English supplier turned out to have also fought with the Partisans during the war and struck up a close friendship with Mimica.

It was widely distributed in Italy, and played alongside another epic, Akira Kurosawa's 1975 Derzu uzala, which was brought by the same distributor at the same time. Mimica had long since had an admiration for Kurosawa, going back to his pioneering film Rashomon (1950), which introduced Japanese cinema to the West. Mimica even envisioned the fight scene in Događaj, which takes place in mud and shallow water, as a homage to the great Japanese director. In Mimica's eyes, this was reciprocated later:

I had the opportunity to meet Mr Kurosawa when the Italian version of the films [Sedlačka buna 1573 and Derzu uzala] played in Milan. Sedlačka buna 1573 had a big huge mediaeval battle, between the farmers and the feudal soldiers. And Kurosawa saw that and congratulated me on the performance of that battle, and I told him that for me it was a huge historical battle between two empires: the rich and the fed ones, and their empire, and the poor and hungry ones, and their empire. I told that to Kurosawa and he didn't understand, because in Japanese thinking such a social approach was completely alien to him. But five years later, I saw his film Kagemusha [1980] which he did for [Francis Ford] Coppola and I was satisfied to see that the structure of the final battle was identical to that in Sedlačka buna 1573.Between two gods

His next film was Banović Strahinja (1981), a film named after its main protagonist. Describing his starting point for the film, Mimica said:

It's a folk poem that's very popular in all the former Yugoslav republics. While researching the film, I found some 40 versions as each nation has its own variant, but the source of this poem is from India .

Mimica chose one version that caught his eye that brought out not the Christian tradition but the ancient Bogumil one. The Bogumils believe that there are two gods, one of light and one of darkness. In the poem this translates into a woman who is torn between two such "gods" in the form of two men, her husband and a conqueror, whom she eventually choses. The film is particularly popular with women.

Banović Strahinja was the last film that Mimica made. But, why? At the age of 58, he was by no means old in film-making terms. Neither was his work unpopular, domestically or abroad. Did he run out of inspiration? Or was he defeated by the incessant bureaucracy (so criticised in his early films) necessary to make features? Or could the answer lie in the fact that 1981 was one year after Tito's death? Did the new administration which emerged in the wake of marshall's death unfavorably look down on Mimica as somebody too closely associated with the ancien regime?

Whatever the reason, Mimica's response to my simple question on why he stopped making films indicate that the reason is a personal and, perhaps, difficult one for him: "No comment."

Mimica is not a widely known director, and the Pula retrospective was a welcome opportunity to review the career who has had a remarkable career in Croatia and abroad (particularly Italy). Although some of his films are indeed now dated in their approach (ever the disadvantage of being cutting edge), none of them are self-indulgent or allow their formal qualities to overshadow their interest in human behaviour. And if some of his films seem slightly dated in thier style now, it is only because they are the Croatian version of a contintent-wide 1960s spirit in the air.

Andrew James Horton, 2 November 2001

Moving on:

- Browse through the CER eBookstore for electronic books

- Buy English-language books on CEE through CER

- Return to CER front page