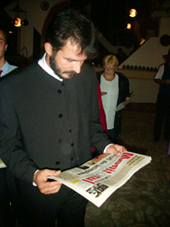

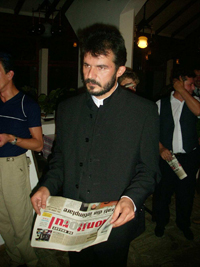

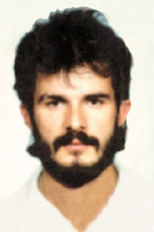

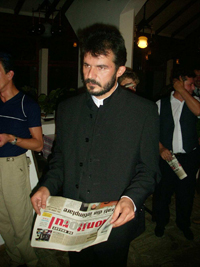

In a tiny, cozy office in an old, small, renovated house on Rosiorilor street in the central Romanian town of Braşov, a dark-eyed 33 year-old man, wearing jeans and a black journalist's vest full of pockets, is running his business from a small black wooden desk on which there are a laptop and an ashtray full of Lucky Strike butts. A few copies of the Romanian daily Monitorul are pinned to the wall right in front of his desk by an old terracotta stove. An engineer by trade, Marius Stoianovici has, however, got stuck in the Romanian print media industry, where he rose through the hierarchy to eventually become the general manager of the local daily Monitorul de Braşov.

A cross between journalist and businessman, Stoianovici is one of a number of members of the Romanian press who have experienced all kinds of tribulations in this period of transition when the ongoing war between the political and economic power on the one hand and the press on the other has become a daily routine. Involved in countless press trials, some of them still pending, with lots of enemies around him and his own newspaper, he struggles to believe that one day the press will become an independent industry, able to make a profit on its own—unlike today, when you must play the sharks' game to survive.

"Obviously, I've made compromises," Stoianovici said. "As a journalist I don't believe I did, but then as a manager... How can you not make compromises when on each pay day almost 100 employees are waiting for their ridiculously small wages and you have no money in your bank account? Can you refuse an advertising contract offered, apparently, without any hidden interests behind it? There were times when I, personally, didn't succeed in refusing it..."

A difficult start

On 30 March 1990, Stoianovici published his first story in the Braşov-based students weekly Replica. It was an article about his former head of department from ICIM—a construction company from Braşov—who had been dismissed by the management just two months before he was due to retire. The aim of the move was to make room for a former manager of the communist era who had been driven away from the factory by his employees during the December 1989 revolution.

"It was my first story and my first libel trial," Stoianovici remembers. "I was interrogated by police, by the prosecutor's office and, after a troublesome year, I the charges were dropped. This was my first school of journalism and it sparked my desire to work in the press. I thought at that time that it was my duty to continue what had started in 1989, the revolution, and the best weapon seemed to me to be the pen."

A graduate of the engineering faculty of the Braşov—based Transylvania University , Stoianovici also attended the Superior School of Journalism in Bucharest. After Replica, he moved in the early 1990s to the local Braşov-based daily Mesager, where he worked as an editor. He was later involved in the launch of three local dailies, Transilvania Expres, Bună ziua Braşov and Monitorul de Braşov.

The first years of journalism were an insanely tough experience, he remembers. "The first days as a journalist were extremely confusing," Stoianovici said. "On the one hand, lots of people were afraid of journalists and compared them with their pre-1989 counterparts—most of whom had been communist activists. On the other hand, there were people who wouldn't give you information even if you threatened them with death, simply because they were afraid. Anyway, the press was read in huge numbers and, at that time, the major sin of the Romanian journalist was that he was smuggling his own opinion into the story. There was a lot of personal opinion and an extremely small amount of naked information in the stories."

Anyway, the press was read in huge numbers and, at that time, the major sin of the Romanian journalist was that he was smuggling his own opinion into the story. There was a lot of personal opinion and an extremely small amount of naked information in the stories."

The first real challenge for the enthusiastic journalist Stoianovici occurred when he leapt into press management—something of "an imperceptible move," he said. "In the organizational chart of the daily Bună ziua Braşov, the position of manager was non-existent, and because we needed to make the pay rolls, to buy paper, maintain the relationship with the printing house, [deal with] salaries, distribution, promotion, sales, in time, I got to learn all these [tasks] by heart and became, like it or not, a manager," he said.

The way to the top

But the real turning point in his career came, undoubtedly, when he was sacked in 1997 by the owner of Bună ziua Braşov, seemingly on political grounds, and set himself the aim of getting all of the paper's personnel and invite them to work for a new independent daily that he was planning to launch. He did so in 1998.

"The most difficult moment for me was on 17 December 1997, when I was sacked from the position of editor-in-chief of the local daily Bună ziua Braşov and I had to force my colleagues to keep on working and not resign en masse because I didn't have any jobs for them and because we were just before the winter holidays," Stoianovici said. "My biggest satisfaction came on 20 June 1998, when I launched Monitorul de Braşov, a daily that I am still managing and where the whole team that I was talking about came and joined me."

The Monitorul network is a network of 20 local newspapers—3 of them weeklies and 17 dailies—that are laid out, printed and then distributed by four big divisions: Iaşi, Braşov, Cluj and, recently, Bucharest. The total circulation is about 100,000 copies a day, which places the network in third place in the top of newspapers with the highest circulation, right after the national dailies Adevarul and Evenimentul Zilei.

Monitorul de Braşov sells 5500 issues a day, 2000 fewer than the local market leader, the daily Transilvania Expres, according to the latest media surveys. "Because it's an expansive type of newspaper for Romania, and in order to increase its economic efficiency, the owner of the Monitorul brand, Press Group SA, has recently given the papers, in a franchise system, to the managerial teams in the territory and this has stopped the losses and generated some profit for the owner," Stoianovici said. "Time will prove if this formula, which is unique in Romania, is viable."

After joining the Monitorul network in 1998, he became a general manager of the daily Monitorul de Braşov and then a general manager of the Transylvania division of the network. In January last year, he was appointed general manager of the entire Monitorul network. He also headed the advertising agency of the Bucharest-based Nord Est Medianet network and simultaneously held the post of executive director of the national daily Curentul.

A member of the board of, and shareholder in, Press Group SA, Stoianovici has left all Bucharest-related jobs early this year to devote his time to the daily Monitorul de Braşov, a newspaper currently published by Nest Media SRL, in which he holds 95 per cent of the shares through his private company MSTM Consulting. The other five per cent of the shares are held by his wife. He has a third of the shares in the companies publishing the dailies Monitorul de Sibiu, Monitorul de Cluj and Monitorul de Mediaş. He also has 55 per cent of the shares in the company Valahia SRL, which has recently entered the newspaper and magazines printing industry.

They say that Justice is blind

He parted ways with the former owners of Bună ziua Braşov mainly because he refused to make certain compromises at the bosses' request. A kind of political game. He doesn't talk about it. Such conduct had brought him lots of pains before. And he paid a high price: lots of trials and several sentences.

"I'm definitely the most 'sentenced' journalist from Braşov," Stoianovici cynically argued. "I got most of the sentences when, as the editor-in-chief of a Braşov-based newspaper [Bună ziua Braşov], I had the naivety to respond to an invitation by the Romanian president at that time, Emil Constantinescu, to launch a campaign against corruption. The only concrete result was that I was sentenced to pay a penal fine and almost 2 million lei [about USD 100 at that time] in damages to the manager of the bread producer Postăvarul. This happened because I had published a letter signed by a group of employees [of the above mentioned business] who unveiled some abuses in the company."

The harassment continued. "Relevant for the way in which the Romanian justice [system] works is how I was sentenced after the trial launched by the chief of the Braşov revolutionaries [an association of people claiming, some rightfully some not, to have fought in the 1989 anticommunist revolution and asking for certain privileges as a result], Dorin Lazăr Maior, currently a PSD [the ruling party, Partidul Democraţiei Sociale] deputy, who sued me for a [newspaper] column, an opinion I had," said Stoianovici."

Although he withdrew his complaint through a notarised declaration sent to and filed by the court, the Braşov-based court proceeded to sentencing me because that document disappeared from the file. Moreover, my appeal was also rejected because that document—my appeal request—had also disappeared, and the sentence remained irrevocable. My luck was that I discovered that I had been subpoenaed at my former address, which meant that they didn't comply with [granting me] my right to defend myself. I made a contestation and gave the document containing it directly to a judge, and she acquitted me."

Currently, Stoianovici is involved in a six-year-old trial with Sergiu Chiriacescu, the rector of the Transylvania University in Braşov, currently a PSD senator. "He sued me because the newspaper where I was working as an editor-in-chief published a story signed with a pseudonym," Stoianovici said. "Although I and my colleagues eventually disclosed the name of the author, the trial is still going on, and if past experience is anything to go by, they will probably sentence me again."

Suing journalists has become a daily hobby in Romania, mainly among politicians and businessmen who make use of the Penal Code (articles 204-205 punishing libel and insult). There are journalists such as Cornel Nistorescu, the editor of the daily Evenimentul Zilei, who have been involved in hundreds of trials. Those who sue journalists don't run any risks, especially after the 1996 elections, when the Ministry of Justice abolished the decision concerning the stamp fee which plaintiffs used to have to pay when asking for compensation. Thus, one can sue journalists and ask for any compensation because there is no risk of losing anything.

There were discussions in the government to remove libel and slander from the Penal Code and reclassify them as civil law offences, but they reached no conclusion. Prison sentences are usually barred, but the fine remains effective and gets stuck in the journalists' criminal records. It also ruins them financially.

No compromises, no money

If some use the law as a scarecrow to gag the press, others make use of the so-called "economic censorship," a typical phenomenon for the emerging Eastern European press industries. Economic censorship means that the journalist is not allowed to write negatively about, for example, the companies that advertise in the media he works for. "It's a consequence of the economic poverty in the country and part of the daily survival of most publications," Stoianovici explains. "And it's also caused by the fact that not even the advertisers make the difference between an advertising contract and editorial space. Generally, it seems normal to them that one shouldn't write negatively about them once they pay."

"And it's also caused by the fact that not even the advertisers make the difference between an advertising contract and editorial space. Generally, it seems normal to them that one shouldn't write negatively about them once they pay."

It's also linked with the behavior of the Romanian justice system, a set of poorly paid public institutions that have acquired the fame of being quite corrupt. Trying to assist journalists in their fight against this system that is under the thumb of the political and economic power, several professional journalists' organizations have been established in the past years, but they were seemingly unable to solve the problem. "Except for the Romanian Press Club [an association of Romanian publishers], the Society of Romanian Journalists and the Center for Independent Journalists in Bucharest, I don't have any knowledge of other associations which move things further," Stoianovici said.

There are about 20 professional associations of journalists in Romania, such as the Association for Transparency and Free Expression, the Society of Romanian Journalists, the Association of Photo Reporters, the Foundation of Independent Radio Stations and other small local organizations, but none deals exclusively with the legal protection of and assistance for journalists undergoing trials.

In 1999, The American Freedom House, with USAID funds, set up the FreeEx (Freedom of Expression) association, which aims at developing a regional network to monitor the attempts to intimidate or punish journalists and offering assistance to journalists in trouble. Since last year, the association has been receiving funds from the Open Society Foundation Romania and the Romanian Office of the World Bank. Last year, in March, the association set up another organization, the Association for Protecting and Promoting Free Speech (APPLE), whose president, Mircea Toma, said that the new organism would also assist journalists in trials.

War with empty pockets

Although "the relationship between press and the political and economical power has normalized a bit," the independent press still has to play the bloody game, Stoianovici argues. "The time of the biased press has passed and those who didn't understand this saw their circulation go down. Except for some so-called barons of the national press, who knew and still know how to negotiate some fat advertising contracts—for instance, with public companies such as railway company SNCFR—the press has learned that it can't expect anything from the power and it's useless to play the power's game."

However, the fight against the political and economic power, which is committed to gag the press, is getting fierce. "There are very few media which are not under political or economic control," Stoianovici said. "I am not aware whether this policy of the political power to suffocate the independent media happens on purpose or it's only due to a lack of awareness."

Journalists seem to be the most affected. Crazy, cynical guys with empty pockets who sometimes wonder what's keeping them in the game. "The Romanian journalist is a typical person," Stoianovici said. "He never has money. He is sufficiently crazy to attack anyone without caring about the danger. He is cynical because he saw too many things and knows that he is alone in the war against everybody because he isn't actually protected by anyone. […] On the other hand, the press has become more and more menial to political and economic interests mainly because of the crisis that the Romanian economy has been going through."

|

Much is expected from the emerging young generation who has taken the helm and is struggling to get rid of the old activists and practices. "Journalists have become more professional; my generation, the 30-40 years old, took the helm in a dozen of organizations and, paradoxically, most of them are like me, engineers," Stoianovici said. "I believe that the level of professionalism is good, above average; the press has cleaned itself up of the old activists and the kids who took over have learned journalism in their workplaces. This change of generations was needed."

However, the crisis of the press persists, and this stems from the whole economic disaster in which Romania is deeply stuck. Look at the press and you'll see how Romania is doing from an economic point of view. "The everyday circulation of the print media is decreasing mainly because the buying power of population is decreasing," Stoianovici said. "This leads automatically to a slump in the readership of that medium so, implicitly, the vulnerability to all kind of pressures is growing."

That's why to talk about profit in this business is a little bit weird, Stoianovici bitterly suggests. "The media doesn't make a profit yet," he said. "Maybe the barons that I was talking about hitherto. Without blackmailing, advertising contracts pushed through politically, it's not easy to survive. We don't even dream about getting rich."

Marius Dragomir, 5 November 2001

Moving on:

Anyway, the press was read in huge numbers and, at that time, the major sin of the Romanian journalist was that he was smuggling his own opinion into the story. There was a lot of personal opinion and an extremely small amount of naked information in the stories."

Anyway, the press was read in huge numbers and, at that time, the major sin of the Romanian journalist was that he was smuggling his own opinion into the story. There was a lot of personal opinion and an extremely small amount of naked information in the stories."

"And it's also caused by the fact that not even the advertisers make the difference between an advertising contract and editorial space. Generally, it seems normal to them that one shouldn't write negatively about them once they pay."

"And it's also caused by the fact that not even the advertisers make the difference between an advertising contract and editorial space. Generally, it seems normal to them that one shouldn't write negatively about them once they pay."