Over a period of centuries, Wallachian shepherds spread across mountain ridges from the Black Sea to Moravia, permanently transforming the natural environment, economy and culture of the Carpathian Mountains. It all began in the 10th to the 13th centuries in present-day Romania, when shepherds and their flocks of sheep moved to new pastures high in the Carpathian Mountains.

The slopes and ridges of the Southern and Eastern Carpathians began to be used for seasonal sheep farming. This was made possible thanks to a special breed of sheep, called "Wallachian" in the western reaches of the Carpathians. The sheep were small, with rough wool, and were able to withstand the harsh conditions of living in the mountains yet produce relatively high yields of milk.

It is difficult to say exactly why the move from the Romanian lowlands to the highlands occurred. One reason was surely the manner of keeping livestock. We can assume that flocks of Wallachian sheep (and other kinds of livestock as well) pastured on the lowlands, including on barren and even steppe-like pastures. In search of new pasture, this hardy breed of livestock moved to the mountains. Other reasons that are often cited are the destructive raids by Eastern peoples, as well as the continuing threat from the Ottoman Empire.

The early stages

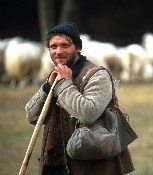

|

| Photo: David McCairly |

Over time, a special way of life developed. From the economic point of view, the introduction of shepherding marked the first extensive use of mountain areas in the region. Other kinds of economic activity at this time, such as hunting, mining, harvesting and processing wood, were only of secondary importance.

Sheep farming was also the first human activity to significantly affect the shape of the Carpathian environment, which until then had remained virtually untouched. Shepherds became a permanent feature of the Carpathians. They adapted themselves to the natural environment and also changed it. The impact of animal husbandry on the Carpathians can only be compared to the later rationalization of forestry that began at the end of the 18th century and the subsequent development of mountain tourism and recreation.

A special manner of keeping livestock developed. Flocks of sheep and smaller numbers of goats pastured in the mountains, far from the permanent settlements of their owners, throughout the summer months. This period—roughly from May to September—coincides with the optimal lactation of sheep. Due to the harsh conditions of mountain living, sheep farming was done exclusively by men, usually in their prime years of life.

Large flocks (1000-head flocks were not exceptional) were pastured in all weather from morning to night, with only a break at mid-day. Nights were spent under the open sky in a large, oval-shaped enclosure constructed of branches and felled trees. In the middle of the stockade there was a primitive shack for the shepherd to stay in.

The main products were dairy, especially cheese. A special product that was developed was a kind of curdled milk, which was produced by seeping the stomachs of young lambs and calves who were raised only on their mother's milk. The seasonal sheep farm was completely self-reliant. In September or October the huge flocks were driven far down the mountains to pasture in the lowlands, often as far away as the Black Sea.

Wallachian colonization

Wallachian colonization refers to the gradual spread of shepherds and their flocks across the Carpathian arc, first to the north and then westwards to Moravia, which occurred over a period of some two hundred years. The main reason for this migration was the search for new pastures.

With the constant increase in the number of livestock, the existing pastures were devastated and became overgrown with inedible weeds. Surely also of help was the fact that the shepherds were well-received in the new areas they moved into and granted various privileges, in return for which they gave the local ruler a "fiftieth," in other words, one dairy sheep, a young infertile sheep, and a lamb for every 50 sheep they pastured on the ruler's land.

The spread of Wallachian colonization across the Carpathian arc took place gradually. In each new place they moved to, the Wallachians gradually assimilated with the local inhabitants, who after a time also adopted sheep dairy farming. Wallachian ways changed considerably under the influence of the local culture and traditions.

As early as the 14th century there is evidence of Wallachian colonists even among neighboring Slavic peoples outside of Romania—seen first in the present-day Transcarpathian Region of Ukraine (Subcarpathian Rus). In the 1400s, Wallachian colonization spread across the entire mountain area of Slovakia as well as the Carpathian regions of southern Poland. By the end of the 15th century it reached the end of its migration in the Moravian area of Valašsko ("Wallachia") and Těšín Silesia, where the last assimilation took place with the local population of Czech peasants.

By the time that Wallachian colonists arrived in Moravia, almost all of the relatively fertile valleys along rivers and large streams had been settled. Forests stretched over a large part of the area and were uninhabited, visited only occasionally by hunters and fishermen, beekeepers, who collected the honey of wild bees from tree hollows, as well as by people looking for wood suitable for making various tools and vessels.

These extensive mountain areas were the site of the last Wallachian colonization, its westernmost tip. The settlement led to the more intensive use of marginal areas, whose low value is attested by the fact that the borders between Silesia, Moravia and Hungary were not clearly demarcated.

Shepherding in Moravia

We can take the area of Hukvald in eastern Moravian as an example. At the beginning of the Wallachian colonization, some 5000 Wallachian sheep were pastured near the border with Hungary (now the territory of Slovakia). They provided their keepers with food and wool for clothing and sometimes also money from sheep that they sold. The ruler who leased them the pastures received a tenth, ie 500 sheep, which the Wallachians drove to the bishop's court at Kromeříž (in German: Kremsier).

In addition to this tribute, the lords also gained capable border guards for the remote mountainous areas of their domains, namely the Wallachians who came with the sheep. In the first period, until the Thirty Years War (1618-48), the Wallachians were not regular subjects. They did not have to do corvée (manorial labor) and ruled themselves according to their own law, the so-called Wallachian Law, which applied in different variations across the Carpathians. At the so-called "Wallachian gathering" they elected a Wallachian vojvod, who became their intermediary in dealings with the ruler.

As already mentioned, in each area they moved into, the Wallachian colonists assimilated with the local populace. Among the specific features of the assimilation process in Moravia and Silesia was the symbiosis with the so-called pasekarská colonization-the settlement of suitable areas in the mountains by peasants from the valleys below.

The peasants gradually transformed mountain areas into fields, meadows, and pastures; with time they erected seasonal settlements and farm buildings, before finally settling in the area permanently. These areas were called paseky ("clearing") and their permanent residents were called pasekaři. It was this group of people that were the first to adopt sheep farming from the Wallachians.

During the 1600s and 1700s, a form of organization of sheep farming was established that continued until the 20th century. The majority of the people living in the piedmont areas began keeping sheep. They cared for them during the winter. Then, in May, when sufficient grass was growing on the mountain meadows, the sheep of several farmers were collected together into one big flock.

The large flock was driven to a sheep farm, where it was taken over by professional shepherds&—a shepherd (bača) and herdsmen (pasáci), the so-called "Wallachians" (valaši). The Wallachians looked after the sheep until the end of September and during the summer delivered to the sheep owners an agreed upon quantity of cheese from each sheep.

The influence of the Wallachian colonists on the local peasant population created the specific feature of culture that distinguishes Valašsko from other regions of Moravia. To various extent, this influence is expressed in local agricultural practices, cuisine, men's dress, customs, the development of the dialect and vocabulary, songs, dances, musical instruments, folklore and probably also in the mentality of people living in this area.

The Thirty Years War

Wallachian sheep farming changed considerably over its five hundred years of development. In the first two centuries, pasturing in the mountains was virtually unrestricted. Sheep farmers moved freely in search of new pastures.

The first major change occurred after the Thirty Years War (1618-48), when contracts for leases on land set firm conditions for sheep farming for the first time. This change occurred for both economic and political reasons. As a result of the change in feudal class (including the expulsion of many Czech nobles and the transfer of their properties to mostly German and Hungarian aristocrats) and subsequent restrictions placed on vassals, the Wallachians lost their special rights and privileges, including the right to elect their own vojvod.

The new aristocrats began setting up their own farms and set new conditions for leasing pastures. One could say that, until this time, Wallachians had leased the grass rather than the pastures. Shepherds wandered across the entire territory in search of better pastures. When they found a site, they brought their shepherd's hut or built a new one.

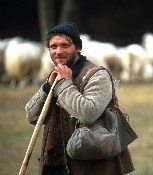

|

| Photo: David McCairley |

They chopped down trees and bushes without limitation. It was a purely extensive, often exploitative, form of farming. Given the relatively small number of flocks in the mountains and the extensiveness of the pastures, the damage the shepherds and their flocks caused was limited. The forest quickly reclaimed any areas that had been destroyed.

Contemporary documents describe the area of eastern Moravia (the Bezkydy Mountains) as virgin land. Irregular, mostly mixed forests alternated with grassy areas that were sparsely covered with solitary or clustered trees and bushes. The grassy areas served as pastures. They were referred to as javořiny (areas of maple trees); a name given by officials in reference to the maples that apparently predominated in these areas. Each javořina had its own name—for example Suchýý Radhošť, Nořičíí, Léskové, etc.

The manner of leasing the pastures changed over the course of the 17th century. A group of sheep owners would acquire a javořina together on which to pasture their livestock. Their contract stipulated how many livestock were allowed and in what composition they could be pastured (eg 230 sheep and 15 cows). The area of the pasture was precisely delimited and restrictions were placed on felling trees.

During the 1700s, the number of sheep grew considerably. For inhabitants of several of the new mountain communities, sheep farming became the most important source of income. In Nový Hrozenkov alone, sheep were pastured on 14 farms; and many settlers kept more than 100 sheep, with an average of about 30 head.

Shepherding in eastern Moravia reached its peak in the 1780s. The blossoming of animal husbandry in the area had a shady underside. Sheep and especially goats destroyed the young forest undergrowth; shepherds burned not only junipers and other bushes, but also large parts of forests in order to expand their pastures; and the number of forest animals dropped considerably. Prohibitions and punishments had little effect.

Decline

Everything changed in the 1790s. From this time onwards sheep farming went into decline. A new competitor appeared in the economies of mountain areas: production of wood for the developing industry. Forest owners, most of them aristocrats, made an easy calculation of how much more profitable harvesting wood was than leasing pastures. It soon became clear that a symbiosis between extensive sheep farming and modern forest management was not possible.

Restrictions were placed on sheep farming in all areas of Moravia and Silesia along the Hungarian border. Forest holdings were consolidated; pasturing in forests, especially in areas with young forest cultures, was strictly forbidden; the expansion of pastures at the expense of forests was strictly controlled. Keeping goats on seasonal sheep farms was forbidden. Finally, the prices charged to lease pastures were increased considerably.

The different approaches toward restricting shepherding in individual areas often decided the further development of sheep farming in that particular location. For example, in Tešín and in Vsetín, groups of sheep herders gained permanent use of certain pastures; in most cases they established cooperatives which were governed by their own rules.

These "shepherding associations" survived into the 20th century. In contrast, in the area of Hukvald, officials and foresters managed to get rid of all seasonal sheep farms by the mid-1900s. The mountain pastures were quickly replaced by spruce monocultures.

The last blow to the development of sheep farming came in the aftermath of the 1848 revolutions. The abolition of so-called servitude (serfdom) included loss of the previous right of vassals to pasture their livestock on their lord's domain. Instead, they received in permanent ownership only a part of the areas they had previously used. Most of the remainder, which remained in aristocrats' hands, was re-forested.

Competition from cheap and quality wool from Australia also contributed to the decline of sheep farming. The spread of agricultural cultivation to higher and higher altitudes was also a factor. Attempts to rationalize sheep farming, as for example by the Moravian agricultural council, were not particularly successful. By the middle of the 20th century, the last remnants of traditional sheep farming had disappeared from Moravia.

A final note regarding the relationship between sheep farming and nature. Having already spoken about pasturing, we still have to discuss stabling. Until the middle of the 19th century very large enclosures were used, in the middle of which there was a shack and a smaller stockade for milking sheep. The sheep spent the night and mid-day in the enclosure (košar). As a result, a large layer of sheep manure quickly developed that was then often used to plant cabbages and grains, usually barley or oats.

After a time, the enclosures with the shed were moved to a new site. At lower altitudes, sheep herding was used for fertilizing meadows and pastures. This form of fertilizing, called košarování (after the word for stockade, košar), was important especially in southern Valašsko, where it helped fertilize fields and meadows that were otherwise difficult to reach. A pair of oxen was hitched to the shepherd's shack, which was equipped with sleds and strong foundations, and moved to the new site.

In today's Moravia, only songs, place names and a few other details remind us of the significant influence shepherding had in shaping the character of the landscape and the culture of people throughout the Carpathian Mountains.

Dr Jaroslav Štika, 23 April 2001

Photos courtesy of David McCairly and Karin Steinbrueck.

Já, bača starý, už nemožem spávat, čujte valasi, já vám budem vyprávjat, ako máte své ovečky opatrovati, aby dobrý úžitok vedely vám dáti. Nedržte ovce dlho v košiaroch,

a nepaste jich v mokrých chotároch,

lebo na nich raste škodných zelin moc,

ked to ovce poždru, dostanú nemoc.

Každú ovečku možete zimovat,

ktorá vysoké čelo bude mat,

nožičky krátúčké, krk jak kon pekný,

bystry zrak, vlny moc, jazyk červený.

Nauku túto dávam vám, čujte,

baču starého nezabúdajte:

lebo ma kašlica velmi dusí,

ked zomrem, jeden z vás bačom byt mosí.

(Folk song from the Moravian-Slovak border) |

|

I, old shepherd, cannot sleep listen Wallachians, I will tell you how you should take care of your little sheep so that they give you good profit Don't keep your sheep long in the stockade

and don't pasture them on wet meadows

as many harmful plants grow on them

if the sheep eat them, they will get sick

Every small sheep you can winter

that has a high brow,

short legs, a neck like a beautiful horse's

sharp eyes, much wool, a red tongue

A tip I will give you, listen,

don't wake an old shepherd

because he has a terrible cough

when I die, one of you has to be a shepherd

|

| |

| |

Na Beskyde velké kopce, pase tam valášek svoje ovce. Na Radošču on ich dójí, valaška mu je pohání. (Folk song from Valašsko) |

|

On the Bezkyd large hill,

the Wallachian pastures his sheep.

On Radošč he milks them,

with a stick he drives them.

|

| |

| |

Pásl ovčák ovce, na zelenej horce, já ráda poslúchám jejich hlasné zvonce (Folk song from Smolina) |

|

A shepherd kept sheep,

on a green mountain,

I enjoy listening

to their ringing bells |

Dr Jaroslav Štika is director of the Wallachian Open Air Museum in Rožnov pod Radhoštem in Moravia (Czech Republic). The article, which has been edited somewhat for publication in Central Europe Review, first appeared in a special issue of Veronica (vol. XIV, 2001/special issue no. 14) devoted to "Shepherding and the Landscape." Veronica, published since 1986, is the bi-monthly magazine of Czech nature conservationists. Contact information: veronica@ecn.cz

Moving on: