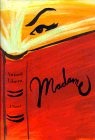

"For many years I used to think I had been born too late," laments the nameless, youthful narrator of Antoni Libera's debut novel Madame, winner of first prize in the prestigious literary competition sponsored by the Znak publishing house.[1] "Fascinating times, extraordinary events, exceptional people—all these, I felt, were things of the past, gone for good."

This feeling, so universal, nevertheless had a very palpable basis in the Polish reality of the early to mid-1960s. For the narrator's (and Libera's) generation, born circa 1949, the 1930s were "a golden age of carefree oblivion," and the war years were "an age of heroic, almost titanic struggle when the fate of the world hung in the balance."

In the narrator's innocent boyhood, even the Stalinist years, just passed, came to be a kind of "great era," though horrific to be sure. He came to see this time, "just because it was so extreme—as something unique, almost out of this world." By the early 1960s, even the heady interlude of the Polish October in 1956—a "Prague Spring"-like thaw—was over, and the tumultuous events of 1968 still lay ahead. The period's official epithet, "the small stabilization," suited it well.

Creative rebellion

Searching for an outlet that would allow room for creative rebellion, the narrator forms a jazz band (music officially frowned upon as an unhealthy import from the degenerate West) and then tries his hand at drama, for which this almost unbelievably multi-talented youth finds he has a special gift. (Libera, incidentally, is a well-known theater director and scholar.)

In his last year of high school, however, the narrator's new French teacher, a beautiful and mysterious woman just over thirty, becomes the focus of his curiosity and creative powers, inspiring within him a deep-felt love in the process.

Madame la Directrice unexpectedly takes over the narrator's French class early in his senior year, and she immediately becomes the subject of intense speculation, not to mention desire, especially among male pupils. Although she is Polish, she is obviously "not of this world": something sets her apart from her surroundings both spiritually and culturally, in addition to the purely external trappings of Western elegance that were so rare at that time (Chanel No 5, fine clothes).

Seeing it as a personal challenge, the narrator sets off to discover as much as he can about the frustratingly enigmatic Madame, motivated at first by a boyish obsession more than anything else.

The narrator's discoveries certainly do not disappoint him. His search starts sensibly with "documents" from the university department where she studied. His real gold mine, however, takes the shape of a family friend, Constant (Konstanty), who turns out to have been a close friend of Madame's father. It is old Constant who relates the story of Madame's birth near the peak of Mont Blanc, her father's adventures in the Spanish Civil War, her mother's death and her fateful return to Poland from France after the war.

All of this helps to explain why she seems out of place and, in uncovering the poignant reality behind the "myth" of the Ice Queen (Madame la Directrice), to make her human. The narrator, as a result, develops a deep empathy with her as a person—and begins to love her in earnest.

The power of words

He wins his "Victory" (her middle name, and the only one we learn), her affection, through words. With no other convenient channel for communication with her, the narrator takes the opportunity offered by class compositions and literature to express his feelings and precocious ideas. In his attempts to "encode" his messages to her, he achieves admirable intellectual acrobatics that not only impress her (though she does not make this publicly known), but also convince him that writing is his true calling.

He discovers that words, if employed effectively, can still move mountains, even in the People's Republic of Poland—whether ferreting out information from unwilling bureaucrats, performing Shakespeare on the stage, haggling with a used bookseller or sparring in class with one's teachers.

A moral message?

Madame is certainly not a novel with an overt political mission and, though it was written after the imposition of martial law (according to the postscript), its main message is not about Communism or opposition, either. Moreover, what it does say about the difficult problem of an individual's attitude toward Communism—the question of resistance versus co-optation—is not entirely clear.

Libera does raise this issue several times, however. From the start, it is quite clear that Madame must be a Party member in order to hold the post of headmistress—though the narrator initially does not seem willing to believe this. Later, Constant and his son, upon hearing that she has become headmistress, are surprised—since this means that she finally "really did it" (that is, joined the Party).

The narrator also finds out that Madame once tried to arrange a fictitious marriage in order to leave the country (for which he had earlier condemned Madame's thesis advisor, who, according to Constant, had succeeded in doing the same thing), and that she seems to be similarly involved with a French diplomat, though we never do learn how she eventually manages to leave for France.

Most shocking for the narrator, however, is his discovery that Madame had even used him through his writing. She submitted an essay for her teaching dossier that he had lovingly written for her, 20 pages of literary allusions linking their two astrological signs, Virgo and Aquarius, and containing "clues" about her life that he had secretly managed to find out, all deftly woven into an impeccably composed French assignment that was supposed to have simply been about "the stars."

|

Times were different

Despite all this, the narrator never passes moral judgment on Madame; in fact, the question seems almost beside the point in her case. Libera's message appears to be that since situations were often far from black and white, it is not necessarily our place to judge people on the basis of the decisions they made under Communism: times were different, and while Madame might have joined the Party for career reasons, she certainly did not become one of "them" in other ways. The author's portrayal of an archetypal Party academician, the intellectually vapid Dr Dołowy, makes this sufficiently clear. (Even his name is related to the word "pit.")

"[T]o say I adored her was to omit something much more important," the narrator tells us near the end of the book,

despite my reservations about some aspects of her personality and her literary tastes... I respected her. She was proud and strong and undaunted, and somehow beyond the influence of the drab, dismal, perverse reality of our People's democracy. With every atom of her being she said no to it; everything about her—her appearance, her behavior, her language, her intelligence—was a resounding, defiant refusal to accept this reality. She was mute testimony to the ugliness and absurdity of our lives, an eloquent reminder that it was possible to live differently.

From its opening pages, this novel wins you over with its literary charms, which Agnieszka Kołakowska's excellent translation ably conveys. Libera's language is a pleasure to read, and he makes the relatively simple story rich in unforgettable images and convincing, well-developed characters, all against the backdrop of an authentic mid-1960s atmosphere evoked so well through aptly chosen details.

Madame's shortcomings—its length, the author's failure to integrate the various tangential (albeit interesting) episodes into the work as a whole and the weak, even superfluous, ending—are far outweighed by its merits, as the many Polish readers of this best-selling first novel have already discovered. The book's greatest success may be that it creates something wonderful out of next to nothing, showing that the modest material of our daily lives can provide us with the stuff of myths and legends—or, at the very least, good story-telling!—if we would only take the trouble to look.

Christina Manetti, 27 November 2000

Moving on:

- Buy Madame from Amazon.com

- Buy this book from Amazon.co.uk

- Archived book reviews

- Browse through the CER eBookstore for electronic books

- Buy English-language books on Central and Eastern Europe through CER

- Return to CER front page

Footnote:

1. Originally published in Polish under the same title by Znak (Kraków, 1999), ISBN 8370069169.