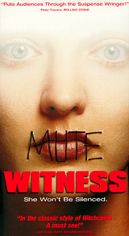

Just how much coherence should viewers expect from a German-financed thriller made by a British-Lebanese director for American distribution, shot in Moscow, and starring US, Russian and British actors, with a well-known Russian actress in the lead role playing the part of a mute American film technician? Considering its extraordinarily tangled production history, the fact that the film—Anthony Waller's Mute Witness (aka Stumme Zeugin, 1994)—was made at all is fairly incredible; the fact that it actually holds together, and succeeds quite ably, makes it an extremely valuable text for exploring the dynamics of cross-cultural cinematic exchange.

Changing time and place

In 1985, Waller—a UK-based director known primarily for his award-winning television commercials—finished work on a screenplay situated in 1930s Chicago, a time when gang power structures temporarily replaced law enforcement agencies as the locus of civil authority. Eight years later, after numerous stops and starts, Waller shifted his story to present-day Moscow, where he had heard the sociopolitical climate was not dissimilar to Prohibition-era Chicago, and where sets and labor could be obtained at a greatly reduced rate. Principal shooting on Mute Witness began in 1993, but things went anything but according to plan: among the unanticipated problems were arbitrary fines in customs, minus-23-degree weather, a diphtheria epidemic and Yeltsin's so-called "October Revolution."

To make matters worse, one of Waller's stars, acclaimed Russian actor Oleg Yankovsky, almost quit out of fear of not speaking English well enough. Despite these and other setbacks, shooting on Mute Witness was eventually completed, and a cameo by none other than legendary British thespian Alec Guinness (whom the director somehow convinced to appear in the picture in 1986, and whose part was shot one morning in Germany) was edited into the final version. Mute Witness premiered in Russia in October 1994 and one year later in the United States, where it garnered praise from reviewers for its technical accomplishment and suspenseful narrative, but was criticized for having a convoluted and largely implausible plot.

Looking in on itself

The film revolves around a mute American special effects coordinator, Billy Hughes (Marina Zudina), who is in Moscow working on a low-budget stalker flick being directed by her sister's boyfriend. In a striking display of self-reflexivity—one that actually preceded Scream and its increasingly derivative offspring by a good two years—we learn that the director chose Russia to shoot his movie for many of the same reasons Waller himself did: inexpensive actors, non-unionized labor and the like.

Sticking around the set after the rest of the crew has gone home for the evening, Billy accidentally stumbles across the making of what she first thinks is a cheap porno flick but quickly determines is a real-life "snuff film," as the female star is brutally stabbed to death by her partner while the cameraman continues shooting.

The pair of killers discover that someone has witnessed their death shoot, and from this point on the picture basically traces Billy's efforts at (i) staying alive with the baddies on her trail, and (ii) convincing others (including her sister's boyfriend and the Russian police) that what she witnessed was not just a fictional murder. To the extent that reviewers were justified in labeling Mute Witness's plot "convoluted," this is due to the introduction of an international crime cartel in the film's final third, as well as an espionage subplot replete with a stolen floppy disk and an undercover detective.

Archetypal heroine

Despite the somewhat clunky shift in gears towards the end of the picture, many critics thought of Mute Witness as little more than an American-style slasher set in Moscow instead of Suburbia USA, with some stylistic nods to Hitchcock thrown in for good measure. This was largely because of its healthy dose of self-reflexivity, tongue-in-cheek humor, bloody murder scenes and its focus on a pretty but prissy woman-in-danger who evinces qualities traditionally conceived of as "masculine" in order to avoid getting killed.

In fact, Billy Hughes can be seen as a composite of the slasher film's androgynously-figured heroines (Hell Night's Marti;  Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2's Stretch; and, most recently, Scream's Sidney Prescott) on the one hand, and the suspense-thriller's handicapped female victims (a blind Audrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark; a blind Mia Farrow in See No Evil; a deaf Marlee Matilin in Hear No Evil) on the other. Upon further investigation, however, it becomes evident that Waller's film actually succeeds in critiquing postmodern American horror fare while still capitalizing on the genre's popularity and instant recognizability.

Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2's Stretch; and, most recently, Scream's Sidney Prescott) on the one hand, and the suspense-thriller's handicapped female victims (a blind Audrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark; a blind Mia Farrow in See No Evil; a deaf Marlee Matilin in Hear No Evil) on the other. Upon further investigation, however, it becomes evident that Waller's film actually succeeds in critiquing postmodern American horror fare while still capitalizing on the genre's popularity and instant recognizability.

The opening scene provides a case in point. In place of the usual slasher prologue, in which the spectacle of hyperkinetic murder is supposed to get the audience "in the mood" for what will soon follow, Mute Witness offers viewers a pale imitation that is as predictable as it is overblown. Before learning that what we have just watched was actually a scene from the B-grade horror film within the film, we shake our heads at how unscary it is and congratulate ourselves on being so familiar with the conventions of the genre—which is precisely what the neo-slasher depends upon and exploits.[1]

There is also the negative portrayal of American director Andy Clarke (Evan Richards), an insensitive, cowardly, spoiled Gen-X'er who fancies himself a horror auteur but can't tell the difference between a real murder and a fake one. Even the clunky transition from slasher film to spy film can be read as a sincere (if problematic) effort on Waller's part to escape the narrative and stylistic constraints of the former.

Cross-cultural horror

If Mute Witness is not quite the film most critics and reviewers took it to be—in addition to the above deviations from the normalities of the genre, the bad guys are much more realistic, and much less personally motivated (being under orders to kill from their gangster don), than the psychosexually traumatized monster-murderers of such traditional slasher fare as Halloween, Friday the 13th and The Eyes of Laura Mars—then in what does its horrifying effectiveness lie?

The answer to this question can be found in Waller's transferring of the original story to present-day Moscow and in his clever decision to have Zudina,

|

The true horror of Mute Witness, which is conveyed with an intensity that belies its lukewarm reception and humble box-office takings, lies in its exploitation of the universal fear of being completely unable to understand others and, at the same time, of being totally incapable of making oneself understood. In this respect, Waller's film leaves its generic legacy far behind and finds itself approaching the rarefied air of such unconventional modern horror classics as Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960), Repulsion (Roman Polanski, 1965), Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977), and Possession (Andrzej Żuławski, 1981).[2] Films which, despite their differences at the level of plot, style and characterization, all make a point of dramatizing that very same fear.

Steven Jay Schneider, 6 November 2000

Retail therapy:

Buy Mute Witness on VHS from Amazon.com (NTSC format)

Buy Mute Witness on VHS from Amazon.com (NTSC format)- Buy Mute Witness on VHS from Amazon.co.uk (PAL format)

- To see clips of Mute Witness before purchasing, visit the Sony Pictures Classics site

Moving on:

- The Kinoeye Archive of articles on Central and East European cinema

- Browse through the CER eBookstore for electronic books

- Buy English-language books on Central European cinema through CER

- Return to CER front page

Footnotes:

1. See Steven Jay Schneider, "Kevin Williamson and the Rise of the Neo-Stalker." Post Script: Essays in Film and the Humanities Vol 19.2 (2000): pp 73-87.

2. Consider also Waller's subsequent directorial effort, An American Werewolf in Paris (1997), the semi-parodic quasi-sequel to John Landis's An American Werewolf in London (1981). Though by no means a classic (anything but!), this film at least reveals a surprising degree of thematic continuity in Waller's work to date.