|

Vol 1, No 18

25 October 1999 |

|

|

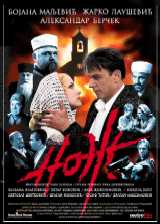

Vignettes of Violence Different attitudes in recent Yugoslav cinema Andrew J Horton Wherever your sympathies lie, you have to admit that this has been a traumatic decade for Yugoslavia, marked by violence, fear and bloody rage. Hardly what one would assume to be ideal conditions for the development of a national film industry. And yet against all odds, Serbian film production has continued and the results have attracted worldwide attention and acclaim. War and international isolation may have hindered production and distribution of Serbian films, but it has at least left directors with plenty to meditate on. Just as it is almost impossible to make a film in Hollywood which is not bathed in an opulence and glamour, so directors from Yugoslavia cannot avoid the underlying social tensions that have driven the country’s politics in the 1990s. This has made recent Yugoslav cinema compelling viewing, whether you be watching cheap trash for a domestic audience or the glossiest productions for international consumption. As part of the recent 7th Raindance Film Festival in London (a showcase for "independent voices" in cinema), seven recent feature films from Yugoslavia were on show to demonstrate the point. Miroslav Lekic's Noz (The Dagger, 1999), billed as the most expensive Serbian film ever, desperately trying to mould itself as an epic love story in the manner of Dr Zhivago or The English Patient. Like its role models, Noz is based on a best-selling book, the novel of the same name by Vuk Draskovic, which the film's publicity goes out of its way to point out is in fact "literature."

Alija's identity is repeatedly challenged, first with the revelation that the Osman family is just a branch of the Yugoviches and secondly when he finds out who he actually is. In the Bosnian war, he meets his brother, who has grown up with a virulent anti-Moslem streak. Illia (as he now is again) persuades his brother that he is in fact an Osman, and the film ends with the two sitting pondering who they are and who they should hate, as the battle rages around them. Noz, like Srdan Dragojevic's international hit Lepe sela, lepo gore (Pretty Village, Pretty Flame, 1995), is attempt to explain how bosom friends became arch-enemies in the Bosnian war. The two are in stark contrast to each other, however. Lepe sela, lepo gore is a blackly humorous and ironic depiction of war which ultimately shows the futility and idiocy of inter-ethnic hatred. Noz, on the other hand, has no room for the comic and glorifies these tensions, showing them to be essential and even heroic. For something which masquerades as a love story, romance is remarkably lacking, and Milica vanishes from the plot at a relatively early stage. Although she remains in the hero's mind, Noz is a story about what goes on between men, brotherly love and bitter rivalry to the death. In this way, war and hatred triumphs over romance as Alija becomes more concerned with who he is than with who he loves. In contemplating his identity Alija's catchphrase becomes "blood is blood," reflecting the film's concerns with justifying blood divisions. If that wasn’t enough, the Moslems are portrayed as barbaric instigators of unprovoked violence against innocent Serbs, while Serb violence, when it occurs, is portrayed as justified revenge. Furthermore, Islamicism is shown as a form of treacherous deviancy. The Moslems are portrayed as desiring a Turkish invasion of Serbia in the 1950s to re-establish an empire in Europe and the relationship between the Osmans and the Yugoviches emphasises that the former are the off-shoots of the latter, who are older, implying they have some form of greater legitimacy. Sex and violence Gorcin Stojanovic's Strsljen (The Hornet, 1998) is a less outwardly jingoistic piece of cinema (and a far cheaper one, too, with Stojanovic coaxing out some very poor acting from some usually fine performers), but ultimately cashes in on society's prejudices and fears. The plot concerns a young Serbian girl who falls in love with an Italian, who introduces her to a lavishly romantic world of Japanese restaurants, expensive presents and luxurious apartments. Just when she thinks she has found perfect happiness, she starts to suspect he leads a double life. Sure enough, this generous and warm-hearted man turns out to be a ruthless Albanian terrorist – code-named the Hornet. Interestingly, this is not just a tale of a love which turns out to be a thin illusion. As he fears his secret is being discovered, Miljiam uses first coercion and then violence to restrain Adriana. This adds a new dimension to their relationship as, in parallel with this, their affair develops from a nervous and even childish romance into a passionately carnal one. The film (sponsored by Avis and Diners Club International) and its equation of macho violence with the sexual admiration of the young and beautiful culminates with the two gazing lovingly into each others' eyes from the opposite sides of a police stake-out after Miljiam brutally murders his brother. Radivoje Andric's Tri palme za dve bitance i ribicu (Three Palms for Two Punks and a Babe, 1998) is a rather more interesting mixture, both teasing society's expectations and living up to them. Tri palme launches off with a sequence which matches the mock newsreel opening of Lepe sela, lepo gore in the hilarity of its satire. An American news reporter comments on how drastic the Yugoslav situation is. The film mocks Western perceptions of Serbian society whilst wryly acknowledging the half-truth behind them, as the presenter reports on inflation of 3 billion per cent a month, how elderly crones are reduced to climbing high trees to forage for fruit and how Serbs have to recycle their condoms. But Andric can't keep up the satirical pace, and the film soon descends into a well-paced but rather mundane plot about a bank robbery. The humour returns in occasional bursts, with the duplicity and criminality of modern Serbian society in general and its banks in particular targets for attack. The film, though, is ultimately driven by the notion that the only way to get your way in a criminal society is to turn criminal yourself. Robbing criminals, as one character points out, is not crime. Although, this message is delivered with a more than light dose of irony, there is an inescapable measure of admiration thrown in as well. Tockovi (Wheels, 1999) employs a similar balance between satire and sincerity. A dark thriller set in a isolated motel, Tockovi also explores the two-sided nature of Serbian society where nobody is quite what they seem. Slick and violent (which has inevitably led the unimaginative to label it "Tarantinoesque"), Tockovi could nearly be a perfect piece of cinematic narration, the fatal flaw coming in the film's limp ending (Click here for a full Kinoeye review). Whatever criticisms you may like to level at Tockovi for glorifying screen violence, they are nothing compared to Boban Skerlic's Do koske (Rage , 1998), which is truly strangled by its self-contradictory aims: a violent film to argue against violent films. With by far the most litres of blood shed of all the films, Do koske revels in a violence that can only be called cinematic in its obsession with style and youthful good-looks. The plot pretext is the kidnapping and torture of Mr Kovac, the local gangland boss (played by Lazar Ristovski, best known for his Blackie in Kusturica's Podzemlje [Underground, 1995]), by a group of disaffected youths who seek revenge for their expendability and worthlessness in society. The film ends with a high body count and a message of peace and reconciliation, but the latter is an artifice to provide a morally acceptable ending to a self-indulgent film. "They have replaced life with movies," comments Kovac in a closing speech which bemoans the influence of American cinema and drugs on youth. And yet it is hard to imagine a film which glorifies American cinema more. With its graphic and sadistic rape scene (which carries the implicit notion that a woman will still love a man even if he sanctions her rape) and the contradiction between its half-hearted message and its substance, Do koske is a morally dubious film. However, it has to be conceded that it is also an incredibly well-made one. It suffers from none of the sloppy immaturity of Strsljen or the excessive matinee melodrama of Noz and emerges as a slick, presentable and - disturbingly - watchable product. One night of madness

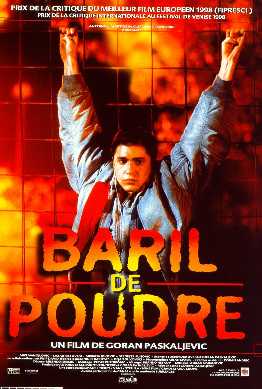

Paskaljevic's aim in Bure baruta was to show how the war in Bosnia affected ordinary people who were not in the front-line. Aided by a strong and gritty script (based on the play of the same name by Dejan Dukovski), Paskaljevic aims to pull a film that depicts the horrors of violence (and especially against women), but without reducing the characters to cardboard stereotypes of evil. The protagonists in Bure baruta are all touchingly human and in some ways we can identify with them and the horrific situations they find themselves in. At the same time Paskaljevic shows how their basic human flaw - the desire for revenge - destroys them, and in this sense Pakaljevic is highly critical of them and their actions. Like Do koske, Bure baruta is a film which uses violence to condemn violence. Bure baruta is, however, a subtler and more challenging film. Whereas Do koske reduces violence, rape and death to screen cliches for the sake of making a visual impression, Paskaljevic's film is more measured in its execution and effect. Although held in a framework of stories which interlock so tightly they cannot be considered realistic, the brutality of the film is horrifyingly non-cinematic. Moreover, the violence is contained not so much in the actions, as in the dialogue and the plots, and Paskaljevic and Dukovski emerge as a keen observers of human behaviour, whereas Skerlic comes over as a skilled manipulator of screen potential. Bure baruta has already had international success, picking up awards at Venice and the European Film Awards, to name but two. Paskaljevic is indeed already an established name in Yugoslav film history with such films as Vreme cuda (Time of Miracles, 1990) and L'Amerique des autres (Someone Else's America, 1995) to his name. However, this may not silence all the critics. Recent years have seen many Yugoslav films undergo re-evaluation and several films previously thought to be anti-Milosevic in their message are now thought to implicitly support the Yugoslav leader. In particular, the whole idea of "Balkan madness" has been criticised as presenting an image of Balkan violence as irrational and therefore unstoppable and uncontainable by the forces of reason. This, the argument goes, is pro-Milosevic in that it advocates violence as an inevitable outcome of the Yugoslav predicament and something which the West cannot control. Furthermore, the obsession with Yugoslav films of trying to pass the blame for violence onto another party has also met with harsh words from critics (See Who Will Take the Blame? by Peter Krasztev writing in Kinoeye). Blame is an important theme in Bure baruta and the characters continually question who is guilty and argue their innocence right up to the final moments of the film's explosive end. Conceivably some critics might find Bure baruta to be pro-Milosevic in this sense. Its notions of Yugoslavia as part of some senseless "Cabaret Balkan" over which the characters have no control and their continual questing for someone to take the blame fit this model. However, the model is flawed. Bure baruta expresses the angst of an individual lost in larger social mechanisms - a common theme in an area of the world where subjugation by one regime after another has been par for the course. To rigidly label the film as automatically being pro-Milosevic is like labelling Kafka as pro-Habsburg. Paskaljevic shows how violence is bigger than individuals and moreover there is some sense of Fate, poetic justice and even morality itself which is larger than violence. The characters are repeatedly lampooned in their belief that they are not to blame for what is happening (quite literally in one scene) and their lack of faith in some morality which is a higher order than the brutality which surrounds them. This is more than can be said for most of the films shown at Raindance, which either showed violence and revenge as the highest form of judgement (Noz and Strsljen), completely dispensed with morality (Tri palme) or had an uneasy relationship with it (Tockovi and Do koske). Andrew J Horton, 25 October 1999 Video clips of Bure baruta with English subtitles can be viewed on-line in real time via the website of the distribuition company Vans. Click on "Domaca produkcija" and then on "Inzerti iz filma. It is necessary to install RealPlayer first.

|

|

![]()

Copyright (c) 1999 - Central Europe Review and Internet servis, a.s.

All Rights

Reserved