|

Vol 2, No 8

28 February 2000 |

|

|

Signs of the Times: Posters from Central Europe 1945-1995 The Imperial War Museum, London, until 7 May 2000 Manchester Metropolitan University, until 7 April 2000 Andrew James Horton The word "bedlam" in English derives from the name Bethlam Hospital, a now defunct Victorian mental institution in south London. Many might think it somewhat appropriate that a former madhouse should now be used for housing a museum dedicated to war, but the Imperial War Museum would probably not appreciate the comparisons. Particularly so since in recent years there have been strenuous efforts to broaden the museum's traditional remit of displaying rusty old weapons, and exhibitions such as From the Bomb to the Beatles have shown how war has effected ordinary people's lives, both during and after its course. Now, following on with this approach, comes an exhibition organised by the Moravian Gallery in Brno which aims to show the how the very active interface between politics and art in Central Europe affected that most ordinary and everyday of visual mediums - the poster.

More than camp and cliché Unintended readings of these works are often hard to avoid, such is the kitsch they are bathed in. With their almost ecstatic young and beautiful faces, it can seem hard to believe that such works as Boris Reshetnikov's Do Not Attack Us and We Will Not Attack You - which depicts a soldier gaining an unusual degree of pleasure from polishing the unfortunately positioned barrel of a cannon - were not deliberate attempts to become homoerotic masterpieces. Nevertheless, such an extensive collection of posters enables the viewer to see the range, subtlety and artistry of political posters from the Socialist Realist period and it is to the exhibition's credit that it succeeds in persuading you to look at these old stereotypes with new eyes and to judge them on their own ground. More interesting though, were the posters that exploded the tired old clichés of Communist-era art. Although obliged to follow the political orthodoxy of the day, Central European artists from the 1960s up to the fall of Communism used their expressive powers to their full limits and a large number of the works on display challenged common notions of officially sanctioned art.

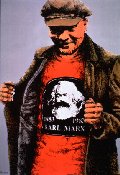

The politics goes on Politics did not become divorced from art with the revolutions of 1989. The message is now more critical, the style has become more anarchic and the humour is more openly biting, but the interest in politics is still very much apparent: the space on a wall where a relief bust of Lenin once hung has the sticker "For Rent" slapped across it, a poster advertising a concert for the victims of Communism shows a white dove trapped in a red-star cage and a slogan invites cyclists to unite as "You have nothing to lose but your chains." However, for all its excellence, its humour and its intrinsic interest value, Signs of the Times is a dense and difficult exhibition. The works are hung closely together two or three high and are hard to appreciate as individual works of aesthetic value.

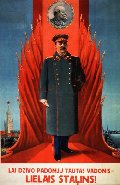

Moreover, the categorisation of the pictures further confuses things. Sections are thematic, with areas including depictions of leaders and internal and external enemies. This means that posters from different political climates (Communism, post-Communism and even one poster from the fascist war years) with different political aims, different national trends and different aesthetic styles are all mixed together. There is also little attention to the subtle but interesting distinction between those artists who used politics as a means to practice art and those who used art as a means to practice politics. A better guide? In this respect, the book accompanying the exhibition Political Posters in Central and Eastern Europe 1945-1995 by James Aulich and Marta Sylvestrová fares rather better, taking a chronological tour of the region before plunging into thematics. The book is also a rather better medium for explaining the essential background to the posters, with its linear text and space for more substantial explanation admirably creating the framework for understanding political posters that is so elusive at the exhibition.

Still, if the exhibition presents a heady mix of clashing ideas and concepts in an at times bewildering manner, it does at least in the process evoke the extraordinary breadth of creativity in political art in Central Europe over the last half century, which constitutes a veritable explosion of ideas. Andrew James Horton, 28 February 2000

Click here to purchase the book Political Posters in Central and Eastern Europe 1945-1995 from the US Click here to buy it from the UK.

|

|

![]()

Copyright © 2000 - Central Europe Review and Internet servis, a.s.

All Rights

Reserved