|

Vol 1, No 20

8 November 1999 |

|

|

O N D I S P L A Y:

O N D I S P L A Y:

A Tattered Testimony Robert Young Usually, the large double doors of the dilapidated Yugoslav Embassy in Prague's Mala Strana are closed up tightly, probably to ward off curious or errant tourists and the occasional unannounced visa-seeker. So the large sign that is now propped up against the building next to the opened door, inviting all to come in, seems more than a little out of place yet is at the same time intriguing. The purpose of the sign is to announce an exhibition entitled Testimonies of NATO War Crimes in Yugoslavia, which features photographs taken by various photographers in and around Yugoslavia during the NATO bombing campaign last spring.

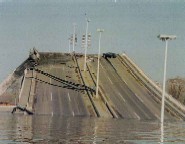

The exhibition room is utterly crammed with pictures, which at first serves to overwhelm the viewer, as the destruction and chaos seemingly protrude from the photos from all directions: shards of torn metal twisted at impossible angles, bridges bent and burned, buildings reduced to rubble and debris, school books rocked off their shelves, empty school desks standing in a sea of broken glass, power grids bent and broken, wires and cables in erratic poses, the infamous television transmission tower fallen and useless. As if the destruction in general were not enough, next to each picture there is a tag denoting the time - down to the hour - that each particular bombing took place and the function of the building before it was destroyed, bringing the subject into the context of time and space. Adding to the poignancy of the photos is the inclusion of the name of each building's architect, placing the subject of each photo into an even more realistic context as well as adding a tinge of irony to the whole exhibit; while the architects' conceptions lie in ruins, the photographers' creations are on display. Notably, the people of Yugoslavia are confined to but a small corner of the exhibition space, where they are shown to be in defiance of NATO: on the streets protesting behind a curious banner that reads (in Cyrillic) "Belgrade is the World," at outdoor rock concerts and spending nights on Belgrade bridges in order to preclude the possibility of having no way to cross the Danube. At times, the array of photographs seems more a tribute to their defiance rather than a testimony to NATO war crimes.

The photos are disturbing, to be sure. They allow the viewer a look into what the streets of Belgrade looked like during and after a night of intense NATO bombing. Although anybody tuned to CNN or BBC could have witnessed such scenes in real time 24 hours a day, the still photos seem to reflect a reality and permanence more deeply than any television camera could have done. However, aesthetics clearly are not the aim of the exhibition. The goal, as is evident from the title of the exhibition, is to provide "testimony" to the "war crimes" committed by NATO during its bombing campaign. Whether or not the exhibition achieves this goal, however, is questionable. Certainly, the bombed out buildings, the broken windows and the parts of bridges jutting out from rivers give the viewer insight into the general destruction that Yugoslav infrastructure incurred, but they do not provide the viewer with answers. On the other hand, a testimony is just that: a presentation of evidence in support of a supposed fact. Nevertheless, the line between warfare and war crimes is clearly very thin.

Furthermore, one photo is markedly out of place - the portrait of President Slobodan Milosevic. Clearly, it is not part of the exhibition but rather of the Embassy decor and shows Milosevic, in typical fashion, removed from the reality he has spun for Yugoslavia. Robert Young, 4 November 1999 To view photos from the exhibition click HERE. The exhibit is on display until 11 November at the Yugoslav Embassy in Prague.

|

|

![]()

Copyright (c) 1999 - Central Europe Review and Internet servis, a.s.

All Rights

Reserved

Education

Education